If there is anyone who still thinks of organisational culture as a soft and fluffy concept, they won’t have read about Baroness Casey’s independent review of culture and standards of behaviour in the Metropolitan Police Service. 25 years after the McPherson report that concluded that the Met was institutionally racist; misogyny, racism and homophobia are still seen to be deeply engrained within its working culture. Even before the Casey Report was published, confidence in policing in London had never been lower, with 71% of respondents to a recent YouGov poll saying that the culture of policing must change. For the wrong reasons, the power of culture has never been so apparent. The Casey Report makes sobering reading; it is thorough in its analysis and powerful in its findings. Whilst the Met’s problems are shocking, the same issues extend beyond London and policing. Last week, the national statistics about police violence against women were revealed, with claims that incidents are not taken seriously or covered up, and very few cases being resolved. And last year, six police forces in England (including the Met) were placed under special measures by Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary. Reports of bullying, misogyny and discrimination in the London Fire Brigade made national headlines in November 2022, followed by stories from other Fire and Rescue Services including sexual abuse and indecent exposure in South Wales, and officers allegedly sharing images of female crash victims in Dorset. Knowing that culture needs to change and knowing how to change culture are two separate things. The recommendations in of the Casey Report are logical and fundamentally sound, as were those in the Francis Report into failings at Mid Staffordshire Hospital in 2013. But will this report change anything? In my previous post ‘It all comes back to culture’, I highlighted how the popular definition of culture as being ‘the way we do things around here’ doesn’t go deep enough, yet that’s exactly the phrase used by Baroness Casey several times in her report. The review certainly “lifts up the stones to see what’s beneath them”, but culture is even more deep rooted than that – it is the complex sets of beliefs, assumptions and expectations woven deep into the fabric of the organisation that drive how people think, act and behave. Why is doing the same thing over again not going to change the culture? Being charged with fixing a toxic culture (as if the responsibilities of being a Chief Constable or Chief Fire Officer aren’t challenging enough), is not an enviable task. When evidence of bullying, harassment, and discrimination is so damning, advocating, in the strongest terms, a zero-tolerance approach is the right place to start. Following that, initiatives are typically started such as new values frameworks, upgraded codes of ethics, EDI training, management development, tougher policies, better reporting systems and improved mechanisms for dealing with complaints. Though well-intentioned, these interventions alone won’t change a toxic culture. Policing already has a robust code of ethics, as does the Fire and Rescue Service. Most organisations that have been found to have toxic culture have values statements, and we’re yet to see a values statement that advocates anything other than sound aspirations about the culture. Applying cultural understanding to blue-light problems The cultural reviews and inspection reports of blue light services we have seen, including Casey, provide strong evidence of destructive combinations of cultural styles at play. What’s missing from the reports and responses is any attempt to measure, define and understand them, or any attempt to break down cultural data into demographics and organisational sub-groups to understand how people experience culture in different ways. Our approach uses the integrated suite of tools that Human Synergistics International (HSI) offer. Human Synergistics is the pioneer in quantifying organisational culture, developed by world renowned psychologists, organisational behaviour specialists and research scientists. Their cultural diagnostics enable leaders to shine a light deep down and across the organisation. For example, one orientation within the HSI research is a ‘power’ orientation. Employees that work in organisations that are high on this style, believe that you have to use force to influence others and be able to get things done, often in order to protect status and security. This can be common in hierarchical organisations, structured on the basis of positional authority, like Police and Fire & Rescue Services. When combined with a ‘dependency’ orientation, which reflects a belief that individuals have little personal control, it is very hard to believe that you can influence cultural change or that your voice will be heard. But a power orientation is not limited to hierarchical power, it can also be the result of: Power based on age or years of experience, for example experienced officers having a strong influence over new recruits. When combined with an ‘approval’ orientation (part of the passive-defensive cluster and characterised by the need to be liked and accepted) this can be a powerfully destructive combination. Power based on a dominant group over a less dominant one, such as men over women, white over minority ethnic, and heterosexual over lesbian, gay or bisexual. This leads to a power play to exclude the minority group. When combined with an ‘avoidance’ orientation (another passive-defensive trait, characterised by shying away from difficult situations and a desire for self-protection) it can discourage inappropriate behaviour from being reported or lead to reports being dismissed or minimised. Although here I have covered only a few cultural combinations linked to power; there are many others I could highlight. The point is, by analysing and understanding culture, it helps to explain what drives the behaviours we find so shocking, and what actions we can take to shift them. It is no coincidence that dysfunctional and toxic cultures are driven by high levels of defensive thinking and behaviour. We’ve seen this across all sectors in recent years where there have been high profile scandals and failings - banking, healthcare, postal services, social care and others. Research into safety records in US nuclear power plants shows that the problems identified in Police and Fire and Rescue Services, and their catastrophic impact, are not unique. The common theme in all cases where mistakes or accidents led to fatal or debilitating consequences was a strong ‘machismo’ culture where crew members feel under pressure to ‘prove themselves’; a passive-defensive form of culture, characterised by the need to gain approval. Crews with the best safety records were proven to have a consistently high level of genuine caring, encouragement, affiliation, and mutual support; all characteristics of a ‘constructive’ culture. This research is consistent with the findings of the LFB review that ‘to belong at the Fire station, you have to earn your stripes, prove yourself and earn the team’s trust’. It also echoes the Chief Inspector’s national findings that ‘watches are considered families by some, but they can exclude others. New members feel compelled to change to be accepted’. How can Work to Be help? As Edgar Schein said ‘cultures will fight to survive’, so truly changing a deep-rooted toxic culture requires an equally deep understanding of the powerful way in which a culture operates within an organisation. At Work to Be, we use our understanding of culture to help organisations uncover ‘what is expected in order to ‘fit in’’. We then help clients to identify the levers for change that will shift the culture from defensive to constructive, and the actions needed to pull these levers. We encourage a holistic view of culture rather than breaking culture down into separate themes and tackling them in isolation from one another. This approach misses the point because an organisation’s underlying culture manifests itself in all problems and challenges. Viewing culture holistically works best as it has multiple impact and achieves lasting change. Inclusivity, belonging, fulfilment and high performance are all positive consequences of a ‘constructive’ culture. If you would like a conversation about your organisational culture, how we could help develop a deeper understanding of culture, and how to shift it in your organisation, Jonathan would love to hear from you.

Have you ever been in a situation where an event triggers a fundamental change in how an organisation behaves and acts, only for everything to return back to normal once the event has passed? The best example of this that I can think of, having worked with several local authorities throughout lockdown, is how councils responded during the pandemic, especially in the early stages. Through what was undoubtedly a challenging and stressful period, especially for those services at the ‘front line’, a powerful and unifying sense of purpose quickly developed. Suddenly the structures that restricted agility and the bureaucracy that slowed down actions and decision making, were removed. People quickly and naturally adapted to vital new priorities, and they talked about feeling energised, trusted and free. Like many organisations, Councils shifted from predominantly on-site to remote working almost overnight, some having to deploy the necessary technology in record timescales. Everyone quickly adjusted. People I spoke to were rightly proud of their adaptability and resilience, and it’s fair to say that society’s perception of the sector rose accordingly. There was much discussion on how the positives must be retained; but, in the end, most aspects of normal service resumed. More than the way we do things around here When we talk with clients about organisational culture, we normally start by asking them what culture means to them. More often than not, that popular definition ‘it’s the way we do things around here’ is mentioned. But it's actually much deeper than that. Culture is what drives how we think, act and behave. In the first phase of lockdown, ‘the way we do things around here’ was fundamentally different. Behaviours and actions changed; but the deep-rooted beliefs and expectations, often built up over many years, didn’t. Human Synergistics, one of the worlds most respected providers of cultural tools and diagnostics, distinguish between ‘climate’ (how things are around here) and ‘culture’ (what’s expected and valued around here). It is an important distinction as it explains why change often doesn’t stick or is short lived. Think of it as being like an iceberg. 'Climate' is what you can see - the part that's above the waterline. This includes how we act, how decisions are made, and how we behave towards one another. For example, when an event brings people together to focus on a common outcome, that’s climate. Culture is under the waterline and not as visible - the deep-rooted beliefs and expectations about our organisation that drive our actions and behaviours. For example, when people are expected or implicitly required to compete rather than cooperate, that’s culture. As Edgar Shein put it, ‘culture is not a surface phenomenon, it is our very core’. Needless to say, culture is much harder to shift than climate – but it is possible. Some organisations think that developing a new set of espoused values and expecting people to follow them is the way to go, then wonder why nothing changes. To change culture, you must seek to understand the culture that exists now, the ideal culture you want to strive for, and then determine steps you need to take to get there. It isn't easy. It takes time and effort. It requires strong leadership commitment the involvement of everyone. But a 'constructive culture' can impact performance and outcomes in powerful ways, so it's well worth the effort.

Is it just me, or is anyone else unconvinced by the growing number of posts and articles, like this recent one by Forbes , heralding the four-day week as ‘the future of work’? Whilst there are aspects of the Forbes article I wholeheartedly agree with, like how we need to prioritise human connection, meaning and purpose, and how we sometimes ‘allow ourselves to sink beneath relentless professional demands and digital distractions without even noticing we are drowning’, in my opinion a four-day work week isn’t the answer to the working challenges of our time. Why do I say that? Firstly, it still reflects an obsession with ‘time’ as the key determinant of how we work. You’ll notice, for example, that in most of the four-day-week trials undertaken (like in Iceland) and examples given (like Atom Bank), that it’s actually five days’ worth of working hours (more or less) compacted into four days, rather than four days of work for the price of five. Which isn’t all that new or trailblazing when you come to think about it. ‘Condensed hours’ are actually already a thing. I have no problem at all with companies implementing, or individual employees requesting, a condensed working week if it works for them, but as an answer to wellbeing and employee experience challenges, it’s too simplistic. Isn't it just switching from a ‘Monday to Friday 9 to 5’ mindset to a ‘Monday to Thursday 9 to 6.30’ one? If we’re seeing this as the future of work, we need to look a bit deeper. For me, work intensification (too much work to do in not enough time) is having the most obvious negative impact on employee wellbeing, and that’s not something that a four-day week is going to solve. Intensifying work more, then giving people an extra day off to recover from it, doesn’t seem to be that well thought through. The four-day week also seems to be based on the premise that work is something we would rather not do if we didn’t have to, so we need to reduce the number of days that we’re required to do it. I don't think that’s true for a lot of people (it isn’t for me), and where it is true, how about focusing our efforts on improving the employee experience rather than shortening it? Much as I enjoy and make the most of bank holiday weekends when they come around, I would rather have a fulfilling and enjoyable job than the equivalent of a bank holiday weekend every week. This obsession with hours and days worked suggests that, when it comes to managing by outcomes, we’ve still got a long way to go. What all the research and analysis gathered throughout lockdown is telling us is that too many organisations still value hours worked, packed out diaries, and a general perception of busyness, and use these things as their subconscious measures of worker productivity. Until we can prove that we’re more sophisticated than that, and become truly outcome-focused, it’s premature to be talking about a default four-day week. Having said all that, the argument that hours worked doesn’t equate to productivity isn’t always true. Maybe it is for knowledge workers, but we’re not all knowledge workers. Not everyone spends most of their working lives in meetings or tapping away on laptops. A lot of the posts and articles I’ve read recently about the four-day week conveniently ignore this fact. I’m a knowledge worker myself, but sometimes I’m embarrassed when people only view the world of work through a knowledge worker’s lens. This lens applies to no more than 50% of us. A four day week for a surgeon would mean 20% fewer operations. For a teacher, it would mean 20% fewer lessons taught (or bigger class sizes to compensate). For a lorry driver it would mean 20% fewer miles covered and 20% fewer deliveries. We would then need to train and recruit 20% more workers for these professions to make up for the lost productivity - and they all have labour shortages already. And even if the NHS could recruit 20% more doctors and nurses, to maintain current salary levels the NHS wage bill would need to increase by 20%. It’s economically naïve to think this would ever happen. So, where would that leave us? It would polarise the working population between those who can and those who can’t work a four-day week without out a drop in salary. And then, who would want to enter vital professions such doctors, nurses, lorry drivers, teachers, care workers and others; the sorts of roles, by the way, that have demonstrated the greatest the value to society throughout lockdown? For me, the potential for polarising the working population is the four-day week campaigners' greatest oversight. Unless someone can come up with answers to the practical and economic questions I’ve posed, the default four-day week is a non-starter. And remember, a genuine four-day week isn't the same as a condensed five-day one. Maybe in the long-term, digitisation will be the catalyst for permanently changing the balance between work and leisure time, but in most sectors we’re not there yet. In the meantime, I’d rather have a healthy debate about what’s really causing the crazy working patterns and practices that are damaging employee productivity, wellbeing and health, than read more articles about a four-day week panacea. So, here’s my plea (but I would love to know what others think); can we please treat the four-day week as no more than a good flexible working option, and not herald it just yet as the future of work.

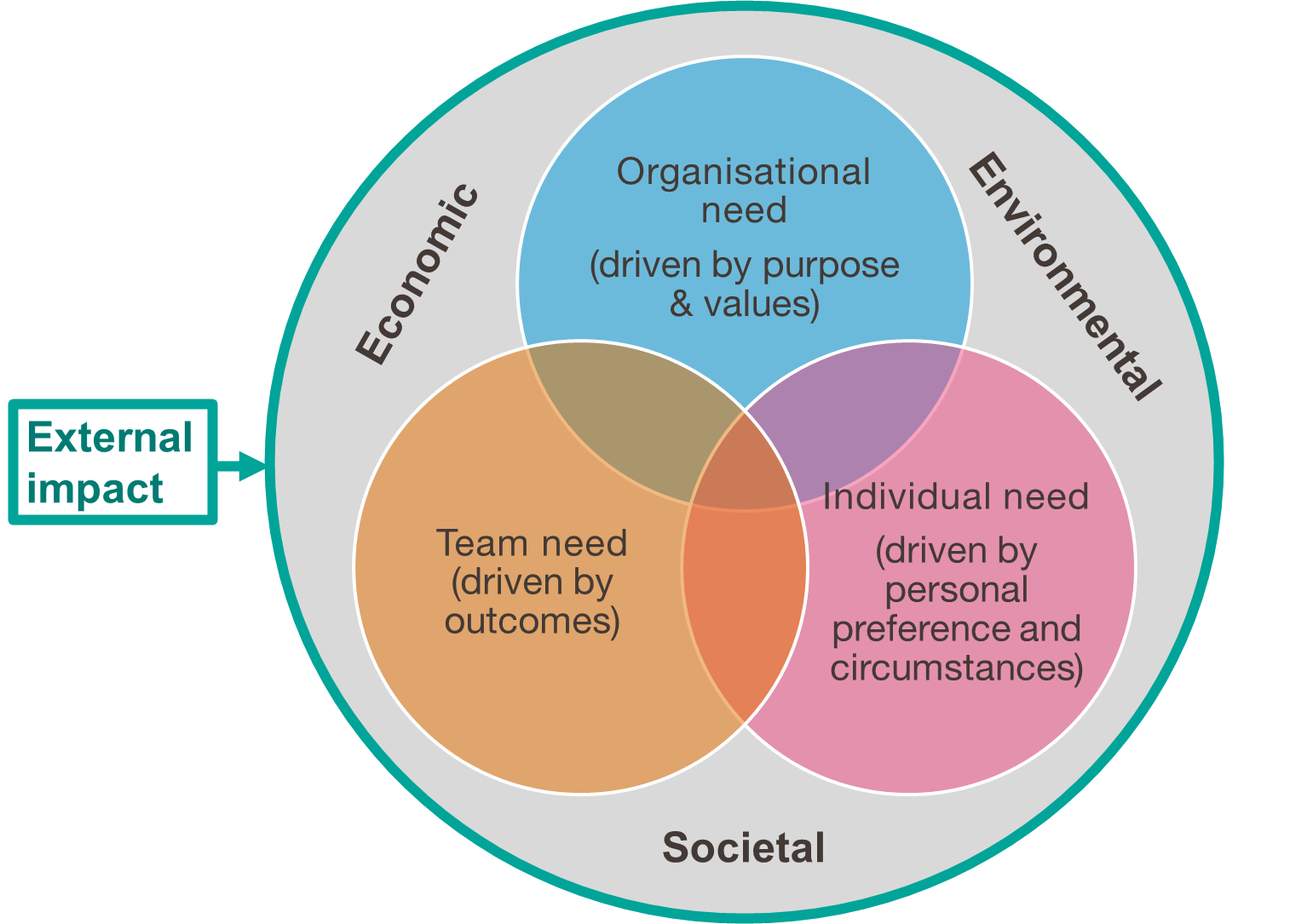

Over the past few months some organisations have announced that it’s everyone back to the office as soon as possible, and others that employees can work from anywhere for as long as they like; but most organisations are not going for either/or, but a hybrid model that lands somewhere in-between. Getting hybrid working right requires up-front thought and planning, balanced with a willingness to experiment, learn, and adapt. Adopting a rigid, ‘one size fits all’ approach to hybrid working, for example by stipulating as company policy days required in the office and at home, and applying it universally, isn’t the way to go (unless everyone you employ happens to carry out exactly the same role and has exactly the same preferences and personal circumstances). Similarly, giving every individual employee total freedom to decide where, when and how they work without any clear vision, guidance or parameters is a recipe for chaos. According to the latest research by McKinsey (mid-May 2021), whilst most executives surveyed agreed that the future of work will be hybrid, less than one-third have a clear vision for hybrid working or a plan in place or communicated. The good news is that it’s not too late, and at Work to Be we developed a simple hybrid working model, adapted from John Adair’s Action Centred Leadership, that balances the needs of the organisation, the team and the individual. However, something was missing from the original model, and I have realised that because the three overlapping circles are all inwardly focused, they don’t encourage a look beyond the organisation level. So, by adding an overarching fourth circle for ‘external impact’, the model is now complete, and takes account of the fact that all organisations are part of something much bigger than themselves and can, through their actions and choices, contribute to (or take away from) that wider picture. Organisational Needs When designing your hybrid working approach, considering the needs of the organisation is a sensible start point. Everything you do should be driven by your purpose and values , and your post-pandemic working model is no exception. It sounds an obvious thing to say, but it’s also often obvious which organisations take a purpose-led approach and which don’t. It is much better to consciously develop working practices that reinforce your purpose and values, than it is to unwittingly reveal what your working practices say about them. Those organisations that announce their (likely top-down) decision to see their people daily in the flesh and reinstate the Monday to Friday commute, could be said to have an obvious single purpose (making money the same way we always did), but not show that they care much for employee wellbeing or limiting their carbon footprint. Similarly, a company that switches to ‘remote first’ to save money on property but installs employee monitoring software as a digital alternative to office visibility, is going to be hard pressed to include the word ‘trust’ in its values statement. A good example of a purpose-led organisation (though not always so good at articulating it) is a local authority. A local council will likely have amongst its top priorities safeguarding vulnerable residents, promoting environmental sustainability, and boosting the local economy. In addition, a likely value will be inclusivity. These priorities and values will need to guide thinking at the organisational level. For example, there is a limit to how well you can safeguard vulnerable residents virtually. You may also be one of your area’s biggest employers, so contributing to turning urban centres into ghost towns because everyone is working at home isn’t very purposeful either. That said, you can’t champion a green agenda if everyone travels into the office five days a week. And you can’t claim to be inclusive if you don’t allow employees to tailor their work patterns or locations to their personal circumstances. So, starting at the organisational level with purpose and values is not always straightforward, but investing the time is worth it. It is then critical to translate your purpose-based organisational needs into simple hybrid working principles that ensure consistency without acting as a straitjacket. Around four or five clear principles will do the trick, setting out to your workforce and the wider world how the way you work will reinforce what you stand for, and providing teams with the flexibility to developing working arrangements that are right for them. Team Needs Establishing needs at the team level and aligning working practices to them is a collective endeavour, not a lone job for the team manager. Too often ‘how we will work as a team’ = ‘how our manager wants us to work as a team’ which leads to resentment, lack of buy-in and, ultimately, a flawed approach because those closest to the work weren’t involved in the process of determining how best to do it. Now is the time for managers to have open and structured conversations with their teams about how a hybrid model can best be applied, and the approach will vary depending on customer requirements, the nature of the work and the required outcomes. What’s right for a data processing team whose work can be done almost exclusively remotely, will be different to an operations team that my require more time on site, and a sales team that might need a mix of focused work at home, office-based collaboration and in-person visits to prospective clients. It is vital that the organisational hybrid working principles are determined first because what is developed at the team level needs to be consistent with these. The key questions for the team to discuss will then focus on the where, the when and the how, such as the balance between home, office and other locations, where and when to connect as a team and beyond the team, and how to use digital tools to better enable hybrid working practices. There are lots of helpful online tools, and articles to help you think this through. For example, Lynda Gratton’s article in Harvard Business Review ‘How to do Hybrid Right’ , provides a simple four-box grid against which you can plot roles depending on the extent to which time and place are constrained or unconstrained. And Boston Consulting Group’s article ‘The How-To of Hybrid Work’ presents a methodology for assessing ‘remote-readiness’ based on a combination of ‘level of collaboration’ (from independent to highly collaborative) and ‘type of work’ (routinized, complex and creative). Developing a set of employee personas, as long as they are kept simple and don’t become an industry, can also help teams determine the most appropriate approach. Individual Needs The clear and consistent message coming out of all the research and survey work about working during the pandemic, globally and across all sectors, is how much people have valued the lifestyle benefits of home working. All of the evidence also suggests that for many tasks, especially concentrated individual work, homeworking is at least as productive as working in an office. Combined with the other ways in which the pandemic has had an impact beyond the world of work, many people are re-evaluating their lives and the part that work plays within it. Whilst work will remain something that provides meaning, challenge and identity, the traditional expectation that many organisations have had over many years that devotion to work comes above all else is being fundamentally challenged. An employee experience reset is taking place, and those organisations that ignore this will likely lose talented people to organisations that understand that wellbeing is a fundamental part of the Employee Value Proposition, not something you only care about during a pandemic. But whilst fewer than 10% of office workers are saying they want to return to the office full-time, a similarly small proportion only want to work from home. The research suggests that there is a deep, human need in most of us to interact with other humans in a physical location; just not every day and not to do tasks that can be done just as well from home. And whilst home working undoubtedly supports greater inclusivity, especially for those with family or caring responsibilities or limited mobility, a remote-only approach can damage inclusivity for the reasons explained in my previous blogpost . A hybrid approach really does provide employees with the best of both worlds. Engaging and involving individual employees in shaping the hybrid working future is therefore critical. This includes reflecting on experiences of lockdown, engaging in conversations and inputting ideas about the team’s future working vision and approach. It requires a mix of collective activities, such as surveys, focus groups and team events, and one-to-one dialogue. And when people are clear about how their work contributes to the outcomes of the team and the priorities of the organisation, they will be unlikely to act like their personal needs should be the sole consideration. External Impact In healthy organisations with a strong sense of corporate responsibility, having a positive impact on the world will already be a key feature of purpose and values, so why do we need the fourth circle? The interconnectedness of our world has never been more obvious. Every output of one system will always have an impact somewhere else, and when we ignore that (as we have often done in the past) the consequences can be devastating. But if we embrace it, we can all contribute to a better world, as individuals and as organisations. The pandemic has brought this to our attention like nothing else, but if we return to an insular approach we will have learnt nothing. That’s why the fourth circle is so important. The three aspects to keep in mind are environmental, economic and societal impact , and there can sometimes be tensions between these so choices about the greater long-term good will need to be made. For example, climate change remains the greatest existential threat of our time and the contribution that lockdown working has had on CO2 reductions from commuter and business travel, particularly by road and air, is significant. Not allowing this to return to pre-pandemic levels needs to be a key goal. On balance, this need is much greater than avoiding the negative economic impact on the motor and aviation industries, and puts the onus on these industries to reinvent themselves for a more sustainable future. Reducing energy consumption in offices and other work locations is also an important environmental consideration, balanced against potentially increasing consumption in people’s homes. Large organisations in particular need to be mindful of the economic impact they have on the areas in which they are based, both in terms of providing local employment and contributing to the hospitality and retail sectors. One of the undoubted benefits for organisations of a more virtual world of work is access to a global job market, but we need to ensure that access to a wider talent pool doesn’t provide a reason not to invest in upskilling existing workers. Digital technologies and artificial intelligence will undoubtedly support the shift to hybrid working, augmenting human talents and giving organisations the opportunity to design better jobs and enhance the employee experience. But if we use these technologies to replace human work rather than augment it, or to tightly monitor human activity rather than to set it free, it will have significant consequences for employee wellbeing and a knock-on impact on public health and wider society. The perfect balance The four elements of hybrid working presented in this article are all important and one shouldn’t be prioritised at the expense of the others. However, as I have explained, they need not be mutually exclusive. Organisational purpose should already be in tune with external impact, and individuals will ideally already be in tune with the needs of their colleagues and customers, and organisational values. Getting a perfect balance isn’t easy, but it’s well worth the effort. Remember too that whist being prepared is important; preparation doesn’t mean predicting every conceivable problem and tying yourself up in knots by putting solutions in place for things that might never happen. The pandemic proved that most of us are pretty adaptable, even when there wasn’t any time to prepare. Keeping things simple and being willing to experimentation, learn and adapt as you go will be the key to hybrid working success. Work to Be is supporting clients to prepare for post-Covid ways of working, including project and change management, employee engagement and leadership development, so please get in touch for an informal chat.

March 23rd 2021 marks the one year anniversary of the start of lockdown in the UK. It’s an important time for reflection, and understandably the main focus will be on the pandemic as a tragedy; the lost lives, the impact on family life, the effect on the economy, jobs and finances. It is a harsh reality that there are some things in life that we can’t influence, and also that the future is often impossible to predict. I’m mindful that writing an article about being prepared for the future runs the risk of appearing insensitive or simplistic in these challenging times; but what’s the point of reflection if we don’t use it as an opportunity to learn and emerge stronger? And because publishing this article coincides with my first Covid jab which, like many people, I see as an injection of hope as much as an injection of a vaccine, I trust you’ll excuse me if I look to the future with optimism. No-one could have predicted what 2020 and the early part of 2021 would have in store for us, in the same way that no-one can predict exactly what will happen in the months and years ahead. It’s so often said that the one thing we can be certain about is uncertainty. And, as the past year proved, those best prepared for uncertainty are the ones most likely to succeed. Even in the sectors hardest hit, like retail and hospitality, those that were thinking ahead and quickest to move to online and home delivery models have been best able to weather the storm. Some have even thrived. For over 10 years I have focused my work on helping organisations prepare for future uncertainty. It’s why I rebranded my business as Work to Be, and have been so passionate about the synergy between people, workplace and technology. I’m proud to have worked with organisations that had the foresight to invest in the future. Flexible working, Better Working, Smart Working, New Ways of Working, Agile Working - whatever they called it, they recognised that the nature of work was fundamentally changing. And when the pandemic hit, even though they couldn’t have predicted it, they were ready to deal with it. What did being prepared look like? Keeping technology up-to-date was one thing - mobile devices, cloud storage, collaboration platforms, business systems designed with the user in mind; you know the sort of thing. The next thing was the workplace; the realisation that many things could be done just as well remotely and offices didn’t have to look like battery farms. And most importantly, I think (but I’m bound to say this, as an HR professional), was how the organisation treated its people; as humans (not as machines), as adults (not as children), as individuals (not as clones), as people who, given a strong sense of purpose and empowering leadership will find meaning in what they do, take personal responsibility and deliver the best possible work (without having to be controlled). Those organisations that have fared best in the last year were thinking and operating along these lines long before the pandemic hit. And it’s reasonable to predict that those that have fared best during the pandemic will be best placed to emerge stronger; and this doesn’t mean picking up where they left things on 23rd March 2020. The Goldman Sachs CEO may have recently referred to homeworking as an ‘aberration that needs to be corrected’, but if he seriously wants to go back to a world where everyone crams into trains and jams onto roads at the same peak times morning and evening to do some things that can just as easily be done on a laptop in the spare room, he needs his head examining! Of course, that’s probably not what he meant (but it made a good headline), and what most people and organisations actually want isn’t ‘all or nothing’ or ‘home versus the office’, but a blend. Proactive organisations are now developing their post-pandemic hybrid model that will allow people to choose the best place to do their best work in the best way they can. But emerging stronger from lockdown isn’t just about having more choice on work location. Again, it’s those cultural elements that will make the biggest difference. A growth mindset will be more important than ever; learning as a continual, natural process, having the freedom to experiment and not being afraid to fail. It’s also about compassionate, human leadership; leaders who demonstrate that being caring isn’t just something you need to do during a pandemic. Wellbeing, inclusivity and the employee experience will need to remain firmly at the top of the agenda. Get the culture right, and the good work will take care of itself. If preparing for the end of lockdown means implementing monitoring and surveillance software or going heavy on policies to keep people under control, as some reports suggest, some organisations might want to think again. In my blog post of November 2018, The Power of Meaning, I wrote about the work of holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl and his inspirational message that if you have a ‘why’ you can live with any ‘how’ or ‘what’. From his unimaginable experiences in Auschwitz, Frankl emerged stronger, approaching life from the point of view that you cannot let events and circumstances beyond your control shape your destiny. As I reflected then: Even if the future is hard to predict, we can get ourselves into a mindset where we can face it with confidence. McKinsey, in their work on leading agile organisations, refer to this mindset as being ‘in the creative’, but that our natural tendency, especially when challenged, is to be ‘in the reactive’. Of course, reacting to the impact of Covid has been all-consuming at times, so being in the creative has been hard. But as we reach the one year anniversary and the light at the end of a very long tunnel starts to shine brighter and gives us something positive to focus upon, it’s still not too late to look ahead, be proactive, summon up energy and a renewed sense of purpose, and face the post-Covid world with strength and confidence. Work to Be, consultancy that combines people, workplace and technology for a better working future.

According to research by Ginger Healthcare, 70% of people cite the pandemic as the most stressful time of their career. In many ways this is unsurprising - Covid-19 is a health crisis of historic proportions and it’s impossible to separate the direct impact of the disease itself - bereavement, concern for our health, concern for loved-ones, financial worries and the impact of social isolation - from how we feel when we’re at work. However, there is growing evidence that suggests that organisations are adding to the direct stress of Covid by applying pre-pandemic thinking and behaviours in a new context of mass remote working. As well as impacting employee wellbeing, it potentially damages our chances of taking the positives from the biggest remote working experiment in history, and progressing on to a hybrid post-pandemic working model that is better for everyone. Even though remote working forced by lockdown isn’t exactly agile, there are many positives. Microsoft’s recent Future of Work Research Report found that only 9% of people want to go back to a traditional office-based working model (incidentally, only 26% want remote only, the rest want hybrid). These figures wouldn’t stack up if there weren’t huge upsides to our experiences of working through a pandemic, not least the time, money and energy saved by not commuting. It is important to say up front that whilst this post is focused on remote working during lockdown (so relates to about two-thirds of us), I recognise that many people are at the ‘front line’ witnessing at first-hand the devastating impact of the pandemic, combined with a real concern about continuous personal exposure to the disease. They may not be as susceptible to feelings of isolation and the difficulty of separating work from home, but the pressures they face daily are far more acute. Tough on stress, not so tough on the causes of stress One of the most positive things about the pandemic, from an employment perspective is that it has taken wellbeing right to the top of the people management agenda. It is being talked about more regularly and openly than ever before, and some of the support and resources that employers are putting in place for their workers are first rate. What concerns me, however, is that whilst there is some great attention going into helping people cope with stressful situations or deal with stress once it has arisen, there is less thought going into how the employee experience may be contributing to poor wellbeing in the first place. I’ll explore this under the themes of work patterns, leadership and inclusion, although it’s actually hard to split them because they are so interrelated. Work patterns Microsoft’s research has found that, in lockdown, we are spending on average 48.5 more minutes at work per day (so, going back to what I said earlier about time saved not commuting, it looks like it’s not us who are benefiting from those extra hours, it’s our employers). They report a 50% increase in working after 6pm, a tripling of weekend working, and 70% of people reporting longer working weeks. You could question whether the extended work day is a result of people working more flexibly, such as taking a couple of hours out in the daytime and making up for it in the evening; but the research (which is partly based on Office 365 activity data, so pretty accurate) suggests that’s not the case. What is actually happening is that many of us are spending our time in back-to-back virtual meetings, so the only time we get to do focused work or deep thinking - often our most creative and productive time - expands into evenings and weekends, leading to fatigue and potential burnout. These relentless work schedules may be partly down to organisational culture and the expectations and pressures of others. But are they also partly self-inflicted? In the same way that we used to stay late in the office to look committed, maybe we are inventing new forms of remote presenteeism? When our work is less visible, does it put pressure on us to appear more productive? And do the very habits that create the perception of productivity, actually end up damaging it? Of course, there’s nothing new about the long hours culture, but lockdown has increased the ‘always on’ element, and made it more difficult to escape work when at home because the workplace is at home. Research by CapGemini supports this, with 56% of respondents to their remote workforce survey fearing that remote work creates a pressure to remain available for work at all times. What research is also telling us is that virtual meetings are more tiring than in-person meetings, so we’re even more drained at the end of a back-to-back meetings day at home than we would be in the office. ‘Zoom Fatigue’, as it has now been named, occurs because virtual meetings are proven to require more focus and mental effort in order to absorb information. So when they’re back to back, with no time in between to recover or think ahead, it’s not good for anyone. One way of responding to all of this is to publish some rules or protocols setting out how people should behave during lockdown (do take regular breaks, do have lunch, don’t work outside these hours - that sort of thing), but this would be missing the point. I’m not suggesting we shouldn’t encourage employees to have breaks or take their annual leave, but if, after a year of mass remote working, the work patterns that are damaging wellbeing have now become ‘normalised’, it’s going to take more than a set of rules to break them, especially if those setting the rules don’t adhere to them. Which brings me onto the theme of leadership. Leadership If the leadership response to the unsustainable work patterns dilemma is ‘we need to give our staff permission to take breaks and a proper lunch’, or worse still ‘we need to tell them that they must!’, it actually reinforces the sort of dependency culture that is likely to be contributing to employee stress levels in the first place. Caring for employees is good, and certainly much better than not noticing that there is a problem, but in a complex, fast-changing world, learning, personal growth and adaptability are the key to success and this is hampered if we are encouraged to always look to those in authority for the answers to everything. This parent-child dynamic doesn’t build resilience. We are learning so many lessons about effective leadership during this pandemic, not least at a global level. And the biggest lesson of all is that compassionate, human leaders who are not afraid to expose their own vulnerabilities and are willing to admit to not having all the answers, achieve the best outcomes. ‘I know best’ doesn’t work. I’m certain that on the whole lockdown has built more trust between managers and their team members, and a realisation that you don’t have to watch over people for them to be productive. That said, there is still a type of manager who feels the need to come up with ingenious new ways to micromanage. These managers may have been in shock for a while when lockdown began, but then discovered that a good alternative to watching over the team in an office is to message them every five minutes at home to keep them on their toes, whilst keeping a constant eye on their online status. Of course, for the employee, that sense that you are always expected to be available, and feeling of being unable to switch-off even for five minutes is, along with everything else they’ve got to deal with during a pandemic, going to massively affect their wellbeing. The CapGemini research supports this worrying trend, with 48% of employees feeling they are being micromanaged in a remote setting (this is 64% in the US) and 59% stating that their organisation has started using work management mechanisms and surveillance technology to monitor them remotely. It also identifies a correlation between this and burnout rates, with 66% of those feeling they are being micromanaged remotely, also feeling burnt out. In his 2018 book about the detrimental impact of modern working and management practices on employee health, ‘Dying for Paycheck‘, Stanford Professor Jeffey Pfeffer concludes that ‘it is beyond doubt that lack of control and autonomy eventually leads to higher burnout and stress levels’. But the known link between lack of self-efficacy and stress is nothing new. I remember once reading that studies into stress levels of WW2 bomber crews found that it was the navigators, whose lives were dependent on the maneuvering skills of the pilot and the aim of the gunners, who suffered the most trauma on their missions because at the moments of greatest danger they felt the least in control. Whilst the consequences may be less dramatic, the same principle applies today. For years many organisations have believed they needed hierarchical structures, complex operating models and rules to dictate how work gets done. Then all of a sudden a pandemic came along and, rather than chaos reigning, we found that people could be trusted to unite behind a common purpose and get on with things, in many ways better than before because they had more freedom to act and decide and weren’t held back by the bureaucracy that was put in place to keep control. Finding that some organisations are inventing and implementing new approaches to micro-management in a remote context is therefore concerning as it doesn’t suggest a mindset shift to a more empowering style of leadership that builds trust and breeds responsibility in return. This will significantly impact employee wellbeing if it is not addressed. Inclusion Feeling valued for who you are, and feeling that you can bring your whole authentic self to work is key to high self esteem and positive wellbeing, and one aspect of inclusion that remote working can impact is our sense of belonging and connection. According to research by Michael Arena at the University of Pennsylvania, we’ve seen an average 15% increase in connections with our closest colleagues since the start of the pandemic, but a 30% drop in ‘bridging connections’; that’s connections within our wider network - something Arena refers to as ‘bridge erosion’. The erosion of networks not only limits our capacity for innovation and creative thinking, it can have a damaging effect on inclusivity, which in turn impacts wellbeing. Social connectedness is a natural human requirement and feeling a sense of belonging to the whole of an organisation and having connections beyond your immediate team are key features of an inclusive culture. It’s therefore a concern that, according to CapGemini’s research, 56% of employees say that they feel disconnected from colleagues and the organisation due to remote working. This is particularly felt by younger employees and new hires. Of course, keeping strong connections with immediate colleagues maintains good morale and can go a long way to reducing feelings of isolation and loneliness. However this becomes a problem when local ties are strengthened at the expense of wider ones, and where lack of diverse thinking or external challenge within a team leads to overconfidence, echo chambers or (worst of all) groupthink. This is particularly dangerous when it applies to senior management teams. Microsoft’s research has found that remote working favours solo work over the collaborative generation of new ideas, and also leads to a decrease in people feeling able to influence decisions in meetings, constructively challenge or express dissenting opinions. This can damage self-esteem, but also lead to poorer decisions as a result of limited inclusion and lack of constructive conflict. And whilst online meetings can be more inclusive to an extent by acting as a social leveller, those less likely to speak up in a traditional setting are even less likely to get a word in edgeways when physical cues and body language are harder to gauge. As Microsoft put it, in an online meeting ‘hierarchies become more conspicuous’. Using parallel chat can mitigate this to an extent, but the chat function doesn’t command the same level of influence as the spoken word and can detract participants from the main agenda if not used effectively. The final, and very important issue around inclusion is how your socio-economic background impacts your ability to work effectively from home. Research from Stanford University found that those with university degrees and top quartile incomes are twice as likely to have a home environment conducive to remote working. So where do we go from here? To some extent, just being more aware of the problems I’ve highlighted helps as we can be more intentional in noticing, avoiding or mitigating against them. And clearly when workplaces open up again and we can balance remote and office-based working and make intentional choices about the setting that best suits the need, some of the problems I have highlighted will ease. Wellbeing strategies need to look beyond providing support for employees at the times they feel they need it, and focus just as much on how the employee experience can act as a cause of stress. And we need to challenge outdated models of leadership and management and focus leadership development activity on open, human leadership that builds trust, agility and resilience. We can also take a more sophisticated evidence-based approach, for example by using activity analytics to support soft data like staff surveys. If we can identify the activity patterns that lead to the best work outcomes and the highest levels of employee engagement, we can seek to build on and replicate these. We can also gain more insight on what patterns are having the most damaging impact on wellbeing in order to adopt a more preventative approach. Just to be clear, I am talking about data at the organisational level and not advocating individual work monitoring and surveillance. The connection between the employee experience and employee wellbeing has been well known for some time and is not unique to working through a pandemic. In 2013 Gallup research in the US discovered that 70% of employees were disengaged at work. The same year (by no coincidence) the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that workplace stress was costing American businesses $300 billion per year, and went on to brand stress ‘the health epidemic of the 21st century’. Covid-19 has presented us with an opportunity to rethink the employee experience and change working lives for the better once the current pandemic is behind us. If we can learn from the positives and negatives of this global remote working experiment and rethink the purpose and design of our workplaces to provide what working from home can’t give us, then that will really help. Work to Be, consultancy that combines people, workplace and technology for a better working future.

I recently read EM Forster's short story ‘The Machine Stops’ which, despite being written over a century ago, is uncannily accurate as a prediction of the world we now find ourselves in. Forster imagines a world where leaving our homes becomes unnecessary, seeing people in the flesh becomes unthinkable, exchanging ideas and knowledge virtually is the mark of productivity, and everything is controlled by an omnipotent global machine. If that sounded familiar pre-Covid, the experiences of the past six months have made Forster’s virtual world even more of a reality, not least the world of work. It could be said that it’s taken a pandemic to achieve in a few months what people like me have been banging on about for the past 10-15 years. ‘Work is a thing you do, not a place you go’ we used to say, as if that summed up quite nicely how our notion of work needed to change. Or so I thought. Certainly lots of things have changed for the better. For example, we’re using mobile technology more effectively and the experience of lockdown has finally busted the myth in many organisations that, for people to be productive, you have to watch over them. But, for me, being stuck behind a desk in my home is no better than being stuck behind a desk in an office, other than that I’m saving time and money and helping the environment by not commuting. And being stuck in back-to-back virtual meetings with no breaks in between is also no better than going from one meeting room to another. My vision for a reinvented version of work wasn’t about replicating all the restrictive practices of office work within my own home! Don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti-home working any more than I’m anti-office working. What I’m anti is ’all or nothing’! And that’s certainly the main message we’re hearing in the organisations I’m working with at the moment. No more than 10% want to go back to the office full time and a similar proportion only want to work exclusively from home. What most people actually want is flexibility and choice. The ability to choose your location and your workspace to best suit your work activities as well as your personal circumstances; including in an office, at home or any other remote location. And most people are also now saying that focused, desk-based work is not the thing they miss about working in an office; that’s the type of work they’re happy to do at home. Which gives us license to rethink the purpose of offices as places to collaborate, innovate and inspire. If this marks the end of desk ratio negotiations and the battery-farm approach to office design, then that gets a ‘like’ from me. I’ve been advocating activity-based office design for years but it always involved a compromise to mitigate against what was portrayed by some as a situation more dystopian than anything EM Forster could dream up - no spare desks! Understandably, the main focus for workspace design currently is within a Covid context; to enable a safe, socially distanced experience at reduced capacity. But this period also provides an ideal opportunity to take a step back, look to the future, and reposition workplaces as strategic assets that reinforce an organisation’s sense of purpose and influence its culture and performance. An important consideration, however, is the impact of workplace transformation on our communities. On the one hand, increased homeworking could drive the regeneration of local neighbourhoods and support independent businesses close to where people live. But what do we do about all the surplus office space this will inevitably create and the economic impact on our city centres? Being instructed by the government that it’s time to go back to work (as if we haven’t been working for the last six months) isn’t the answer. The latest working revolution is well underway and can’t be reversed. However, there must be a way in which we can balance the benefits of increased remote working (including flexibility, work-life balance, reduced congestion and pollution) with the need to prevent our city centres from turning into ghost towns. Humans are social animals and creating vibrant, collaborative offices, easing the pain of the commute and making the journey worth the effort, even if it’s only once or twice a week, will certainly help. Work to Be, consultancy that combines people, workplace and technology for a better working future.

When I ran a workshop for social workers in preparation for a move to a new office and the adoption of agile working a couple of years back, the group was rather hostile. At first I couldn’t understand why, but as the session went on the reason became increasingly obvious. It was the issue of trust. “I’m expected to come back to the office every afternoon to show my face” said one, “when it would save so much time to go straight home and write up my reports”. “And when we’re ‘allowed’ to work from home” added another, “we have to email our manager at the end of the day to list the things we’ve been working on”. So, this was a group of qualified, experienced, competent and committed social care professionals who were being treated like children. They knew that whatever technology and workspace they had access to, if this wasn’t underpinned by a culture of trust, nothing was actually going to change for the better. Social care professionals now have the trust of a whole nation in caring for our most vulnerable through the COVID-19 pandemic and nobody’s suggesting we can’t trust them now! And across the country, in all sectors, managers with a default “if I can’t see you, how do I know that you’re working” approach have suddenly been forced to relinquish control and get used to managing teams remotely. There’s no shortage of practical guidance on remote working, in fact more has probably been written on this in the past five weeks than in the last 5 years. All really helpful stuff. But trust underpins everything else. You can’t build a culture of trust in a few weeks, and the danger will be that when normality resumes, so too will business as usual. It would be such a wasted opportunity. Key to fostering a culture of trust is managing by outcomes. If people have clear goals to which they are committed, they’ll take personal responsibility for achieving them. This Theory Y view was introduced by McGregor back in the 1950’s, and it’s never been as relevant as it is today. ‘When trust is extended’ said Frederic Laloux in Reinventing Organisations, ‘it breeds responsibility in return’. Managing by outcomes means we are also clear on our purpose. It’s not what we do, it’s the value of what we do that matters. That’s another thing that COVID-19 is really highlighting; which organisations and jobs are truly purposeful and add the most value to society. And right now a high proportion of these are in the public sector, which rarely gets the credit it deserves. Take the most obvious of these, healthcare, where doctors and nurses are working so hard at the front-line to keep people alive. You don’t get a clearer, more fundamental or more valuable outcome than that. But purpose can change, and we’re seeing that right now too. Almost all organisations have had to completely rethink their core purpose, re-prioritise, and reallocate resources during this pandemic. In some cases this is as fundamental as keeping in business when there’s no money coming in. And that exposes another myth about how organisations work - that change can’t happen quickly, that it always has to be carefully planned and takes time. In Reinventing Organisations Frederic Laloux talks about how the model of an organisation working like a machine, with a predict and control approach, is no longer relevant (if it ever was). I’ve recently witnessed some amazing examples of how organisations have had to sense and respond , rethinking their priorities and implementing wholesale changes to operations in a matter of days. In fact over these crazy few weeks, the most monumental decisions of my lifetime have been made in days, even hours, when under conventional systems of governance and decision making they would have taken years. Instead of machines, Laloux describes healthy organisations as living systems that naturally evolve, and that’s what we’re seeing in this crisis. In fact, that’s what we’re seeing across the whole economy; an interconnectedness between sectors that’s never been so strong or apparent. It demonstrates the power of having a common cause that everyone believes in and feels part of. When so many lives are at risk and being lost, and so many livelihoods impacted, it would be irresponsible to suggest that COVID-19 is a force for good. But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn positive lessons from it, or recognise the amazing ways that people and organisations are responding. If we can capture and understand these things in the moment, and prepare now for how to sustain them for a better new normal; now that won’t be a bad outcome. Work to Be combines people, workspace and technology for a better working future. We’ll help you to constructively challenge outdated practices, build on the positives of your remote working experience, and underpin it with a trust-based, outcome focused working culture.

Much of my work as a consultant in recent years has been with the Local Government sector, and particularly with London Boroughs. What I love most about the sector is its purpose; it exists for the good of families, communities, vulnerable people, businesses, and the built and natural environment. Social responsibility is at its heart and it attracts people who are motivated by intrinsic rewards and the desire to make a positive difference in the world. The thing that concerns me most about the sector is that it finds it so difficult to tune into a younger generation of workers. And that’s the irony; people who are so motivated by a cause, like climate change or social injustice, still don’t see working for a council as a realistic 21st century career choice. What can it say for the reputation of a sector, when it does so much that is meaningful but fails to attract the generation that is most energised by meaningful work? I’m not saying the local government sector hasn’t made attempts to attract younger people through better branding, use of social media, an improved candidate experience, improved workspaces and technology, and the use of graduate and apprenticeship schemes. But the sector still has an age profile far more skewed towards the retirement end of the age spectrum than the private sector, and a percentage of 16-25 year olds that is a fraction of the overall UK population in the same range. I believe the problem lies in a mismatch between purpose (the why), which ought to be so appealing to young people, and working practices and behaviours (the how), which in many cases are still firmly rooted in the last century. I’ve seen many examples of this: - Young people care about the environment, but most Council’s still print phenomenal volumes of paper - Young people want their office environment to be vibrant and creative, but there is still an obsession with cramming in rows and rows of desks. - Young people highly value flexibility and work-life balance, but there is still an obsession with time recording systems and being seen, rather than outcome-based working. - Young people are brilliant social networkers, but councils still organise themselves in functional silos. - Young people never use email outside of work, but are compelled to use it as the default method of communication in a council office. - Young people want to experiment with different technologies, but many councils impose strict restrictions on what they can and can’t do on a council device. - Young people want a varied career that will include working for multiple organisations in multiple sectors in multiple places on multiple types of contracts, but Local Government still has a reward system designed for the baby-boomer generation and a job for life. There are also many examples of good practice and traditions being challenged, but these apply to specific local authorities going it alone. In fact, Councils seem to like competing against each other to be more of an ‘Employer of Choice’ than their neighbours. What they should be doing is pooling resources and working together for the good of the overall sector. The sector also needs to think long-term, but short-term thinking dominates; driven in particular by financial pressures and changing political priorities. The world of work is fundamentally changing, and someone needs to be looking five years ahead, or even ten. Who’s future-proofing the local government workforce for a very different working future where a sense of meaning and continual reinvention will be the key to success, and in which attracting a new generation of workers will play a vital part? Nobody, as far as I can see. So, a fundamental and co-ordinated rebranding on a national scale is urgently needed if local government is to compete with the private sector for our brightest young stars. Pockets of progress here and there isn’t enough. But there’s not much evidence that anything like this is going to happen anytime soon. And whilst it may be a controversial thing to say, a lot of people currently responsible for changing the sector are products of the system that needs to change. It’s not a criticism of those people; it’s natural to look at problems through a lens shaped by personal experience. I’m just suggesting that more of an external perspective is needed to get the sector to ‘think different’ (as one of the world’s most successful purpose-focused brands puts it). And by ‘external perspective’ I don’t mean bringing in one of the usual big consultancies at high expense; this already happens in spades and hasn’t made a blind bit of difference to the reputation of the sector as far as I can see. What I’m suggesting is some kind of highly creative external intervention. And the place for them to start is ‘purpose’. Jonathan Smale is Founder and Lead Consultant of Work to Be, working with organisations to create a better working future.

There’s no doubt about it, the digital era requires a fundamental transformation in how organisations operate. Digital strategies and roadmaps are important, but they’re not enough. To achieve lasting transformation you have to focus equally on your most valuable resource; people. And that’s where the problem lies. There’s no shortage of research on this issue. McKinsey, IBM, Capita, PA Consulting, the CIPD and many others all draw the same conclusion; that HR and OD functions in many organisations are still viewing the world of through a 20th Century lens and are not sufficiently engaged in the digital transformation journey. For example, in their latest research paper ‘Strategies for Building and Maintaining a Skilled Workforce’, IBM concluded that ‘most organisations have not proactively attacked the problem’ and ‘have not moved beyond traditional hiring and training strategies’. Many people would agree with these conclusions, but a lot of organisations still struggle to understand what it means for them in practical terms, and what to do about it. Most digital strategies mention people and culture, but are light on information about what needs to change and how. And many people strategies talk about technology, but fail to articulate in practical terms the crucial role HR and OD needs to play in achieving an organisation’s digital ambitions. There are digital maturity models, and HR maturity models, but no model or assessment tool that I’m aware of that connects the two in a comprehensive and pragmatic way. Until now. Work to Be has developed a people-focused digital maturity model and assessment tool that tackles the people and cultural aspects of digital transformation head-on. Its themes include culture, organisational design, strategic workforce planning, talent acquisition, digital leadership and skills development. It articulates what maturity looks like, measures current maturity levels, provides a benchmark, enables you to develop practical improvement plans, and measures progress. IT and HR people are drawn to their professions for different reasons and talents, and do not always form the most natural of collaborators. More often than not, they develop their strategies and roadmaps independently of each other. But when their thinking and efforts combine, real transformation happens. It’s time to for HR and OD to join the digital transformation journey! Contact us now for further information and an initial free consultation .

If there is anyone who still thinks of organisational culture as a soft and fluffy concept, they won’t have read about Baroness Casey’s independent review of culture and standards of behaviour in the Metropolitan Police Service. 25 years after the McPherson report that concluded that the Met was institutionally racist; misogyny, racism and homophobia are still seen to be deeply engrained within its working culture. Even before the Casey Report was published, confidence in policing in London had never been lower, with 71% of respondents to a recent YouGov poll saying that the culture of policing must change. For the wrong reasons, the power of culture has never been so apparent. The Casey Report makes sobering reading; it is thorough in its analysis and powerful in its findings. Whilst the Met’s problems are shocking, the same issues extend beyond London and policing. Last week, the national statistics about police violence against women were revealed, with claims that incidents are not taken seriously or covered up, and very few cases being resolved. And last year, six police forces in England (including the Met) were placed under special measures by Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary. Reports of bullying, misogyny and discrimination in the London Fire Brigade made national headlines in November 2022, followed by stories from other Fire and Rescue Services including sexual abuse and indecent exposure in South Wales, and officers allegedly sharing images of female crash victims in Dorset. Knowing that culture needs to change and knowing how to change culture are two separate things. The recommendations in of the Casey Report are logical and fundamentally sound, as were those in the Francis Report into failings at Mid Staffordshire Hospital in 2013. But will this report change anything? In my previous post ‘It all comes back to culture’, I highlighted how the popular definition of culture as being ‘the way we do things around here’ doesn’t go deep enough, yet that’s exactly the phrase used by Baroness Casey several times in her report. The review certainly “lifts up the stones to see what’s beneath them”, but culture is even more deep rooted than that – it is the complex sets of beliefs, assumptions and expectations woven deep into the fabric of the organisation that drive how people think, act and behave. Why is doing the same thing over again not going to change the culture? Being charged with fixing a toxic culture (as if the responsibilities of being a Chief Constable or Chief Fire Officer aren’t challenging enough), is not an enviable task. When evidence of bullying, harassment, and discrimination is so damning, advocating, in the strongest terms, a zero-tolerance approach is the right place to start. Following that, initiatives are typically started such as new values frameworks, upgraded codes of ethics, EDI training, management development, tougher policies, better reporting systems and improved mechanisms for dealing with complaints. Though well-intentioned, these interventions alone won’t change a toxic culture. Policing already has a robust code of ethics, as does the Fire and Rescue Service. Most organisations that have been found to have toxic culture have values statements, and we’re yet to see a values statement that advocates anything other than sound aspirations about the culture. Applying cultural understanding to blue-light problems The cultural reviews and inspection reports of blue light services we have seen, including Casey, provide strong evidence of destructive combinations of cultural styles at play. What’s missing from the reports and responses is any attempt to measure, define and understand them, or any attempt to break down cultural data into demographics and organisational sub-groups to understand how people experience culture in different ways. Our approach uses the integrated suite of tools that Human Synergistics International (HSI) offer. Human Synergistics is the pioneer in quantifying organisational culture, developed by world renowned psychologists, organisational behaviour specialists and research scientists. Their cultural diagnostics enable leaders to shine a light deep down and across the organisation. For example, one orientation within the HSI research is a ‘power’ orientation. Employees that work in organisations that are high on this style, believe that you have to use force to influence others and be able to get things done, often in order to protect status and security. This can be common in hierarchical organisations, structured on the basis of positional authority, like Police and Fire & Rescue Services. When combined with a ‘dependency’ orientation, which reflects a belief that individuals have little personal control, it is very hard to believe that you can influence cultural change or that your voice will be heard. But a power orientation is not limited to hierarchical power, it can also be the result of: Power based on age or years of experience, for example experienced officers having a strong influence over new recruits. When combined with an ‘approval’ orientation (part of the passive-defensive cluster and characterised by the need to be liked and accepted) this can be a powerfully destructive combination. Power based on a dominant group over a less dominant one, such as men over women, white over minority ethnic, and heterosexual over lesbian, gay or bisexual. This leads to a power play to exclude the minority group. When combined with an ‘avoidance’ orientation (another passive-defensive trait, characterised by shying away from difficult situations and a desire for self-protection) it can discourage inappropriate behaviour from being reported or lead to reports being dismissed or minimised. Although here I have covered only a few cultural combinations linked to power; there are many others I could highlight. The point is, by analysing and understanding culture, it helps to explain what drives the behaviours we find so shocking, and what actions we can take to shift them. It is no coincidence that dysfunctional and toxic cultures are driven by high levels of defensive thinking and behaviour. We’ve seen this across all sectors in recent years where there have been high profile scandals and failings - banking, healthcare, postal services, social care and others. Research into safety records in US nuclear power plants shows that the problems identified in Police and Fire and Rescue Services, and their catastrophic impact, are not unique. The common theme in all cases where mistakes or accidents led to fatal or debilitating consequences was a strong ‘machismo’ culture where crew members feel under pressure to ‘prove themselves’; a passive-defensive form of culture, characterised by the need to gain approval. Crews with the best safety records were proven to have a consistently high level of genuine caring, encouragement, affiliation, and mutual support; all characteristics of a ‘constructive’ culture. This research is consistent with the findings of the LFB review that ‘to belong at the Fire station, you have to earn your stripes, prove yourself and earn the team’s trust’. It also echoes the Chief Inspector’s national findings that ‘watches are considered families by some, but they can exclude others. New members feel compelled to change to be accepted’. How can Work to Be help? As Edgar Schein said ‘cultures will fight to survive’, so truly changing a deep-rooted toxic culture requires an equally deep understanding of the powerful way in which a culture operates within an organisation. At Work to Be, we use our understanding of culture to help organisations uncover ‘what is expected in order to ‘fit in’’. We then help clients to identify the levers for change that will shift the culture from defensive to constructive, and the actions needed to pull these levers. We encourage a holistic view of culture rather than breaking culture down into separate themes and tackling them in isolation from one another. This approach misses the point because an organisation’s underlying culture manifests itself in all problems and challenges. Viewing culture holistically works best as it has multiple impact and achieves lasting change. Inclusivity, belonging, fulfilment and high performance are all positive consequences of a ‘constructive’ culture. If you would like a conversation about your organisational culture, how we could help develop a deeper understanding of culture, and how to shift it in your organisation, Jonathan would love to hear from you.

Have you ever been in a situation where an event triggers a fundamental change in how an organisation behaves and acts, only for everything to return back to normal once the event has passed? The best example of this that I can think of, having worked with several local authorities throughout lockdown, is how councils responded during the pandemic, especially in the early stages. Through what was undoubtedly a challenging and stressful period, especially for those services at the ‘front line’, a powerful and unifying sense of purpose quickly developed. Suddenly the structures that restricted agility and the bureaucracy that slowed down actions and decision making, were removed. People quickly and naturally adapted to vital new priorities, and they talked about feeling energised, trusted and free. Like many organisations, Councils shifted from predominantly on-site to remote working almost overnight, some having to deploy the necessary technology in record timescales. Everyone quickly adjusted. People I spoke to were rightly proud of their adaptability and resilience, and it’s fair to say that society’s perception of the sector rose accordingly. There was much discussion on how the positives must be retained; but, in the end, most aspects of normal service resumed. More than the way we do things around here When we talk with clients about organisational culture, we normally start by asking them what culture means to them. More often than not, that popular definition ‘it’s the way we do things around here’ is mentioned. But it's actually much deeper than that. Culture is what drives how we think, act and behave. In the first phase of lockdown, ‘the way we do things around here’ was fundamentally different. Behaviours and actions changed; but the deep-rooted beliefs and expectations, often built up over many years, didn’t. Human Synergistics, one of the worlds most respected providers of cultural tools and diagnostics, distinguish between ‘climate’ (how things are around here) and ‘culture’ (what’s expected and valued around here). It is an important distinction as it explains why change often doesn’t stick or is short lived. Think of it as being like an iceberg. 'Climate' is what you can see - the part that's above the waterline. This includes how we act, how decisions are made, and how we behave towards one another. For example, when an event brings people together to focus on a common outcome, that’s climate. Culture is under the waterline and not as visible - the deep-rooted beliefs and expectations about our organisation that drive our actions and behaviours. For example, when people are expected or implicitly required to compete rather than cooperate, that’s culture. As Edgar Shein put it, ‘culture is not a surface phenomenon, it is our very core’. Needless to say, culture is much harder to shift than climate – but it is possible. Some organisations think that developing a new set of espoused values and expecting people to follow them is the way to go, then wonder why nothing changes. To change culture, you must seek to understand the culture that exists now, the ideal culture you want to strive for, and then determine steps you need to take to get there. It isn't easy. It takes time and effort. It requires strong leadership commitment the involvement of everyone. But a 'constructive culture' can impact performance and outcomes in powerful ways, so it's well worth the effort.